Has the Clean Air Act done more to fight crime than any other policy in American history? That is the claim of a new environmental theory of criminal behavior.

In the early 1990s, a surge in the number of teenagers threatened a crime wave of unprecedented proportions. But to the surprise of some experts, crime fell steadily instead. Many explanations have been offered in hindsight, including economic growth, the expansion of police forces, the rise of prison populations and the end of the crack epidemic. But no one knows exactly why crime declined so steeply.

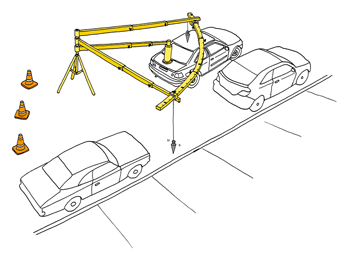

The answer, according to Jessica Wolpaw Reyes, an economist at Amherst College, lies in the cleanup of a toxic chemical that affected nearly everyone in the United States for most of the last century. After moving out of an old townhouse in Boston when her first child was born in 2000, Reyes started looking into the effects of lead poisoning. She learned that even low levels of lead can cause brain damage that makes children less intelligent and, in some cases, more impulsive and aggressive. She also discovered that the main source of lead in the air and water had not been paint but rather leaded gasoline — until it was phased out in the 1970s and ’80s by the Clean Air Act, which took blood levels of lead for all Americans down to a fraction of what they had been. “Putting the two together,” she says, “it seemed that this big change in people’s exposure to lead might have led to some big changes in behavior.”

Reyes found that the rise and fall of lead-exposure rates seemed to match the arc of violent crime, but with a 20-year lag — just long enough for children exposed to the highest levels of lead in 1973 to reach their most violence-prone years in the early ’90s, when crime rates hit their peak.

Such a correlation does not prove that lead had any effect on crime levels. But in an article published this month in the B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, Reyes uses small variations in the lead content of gasoline from state to state to strengthen her argument. If other possible sources of crime like beer consumption and unemployment had remained constant, she estimates, the switch to unleaded gas alone would have caused the rate of violent crime to fall by more than half over the 1990s.

If lead poisoning is a factor in the development of criminal behavior, then countries that didn’t switch to unleaded fuel until the 1980s, like Britain and Australia, should soon see a dip in crime as the last lead-damaged children outgrow their most violent years. According to a comparison of nine countries published this year by Rick Nevin in the journal Environmental Research, crime rates around the world are just starting to respond to the removal of lead from gasoline and paint. “It really does sound like a bad science-fiction plot,” says Nevin, a senior adviser to the National Center for Healthy Housing. “The idea that a society could have systematically poisoned its youngest children with the same neurotoxins in two different ways over the same century is almost impossible to believe.”

The magnitude of these claims has been met with a fair amount of skepticism. Jeffrey Miron, a Harvard economist, wonders how lead could have had such a strong effect on violent crime while, according to Reyes, it showed almost no effect on property crimes like theft. He also doubts that the hypothesis could explain the plunge in the U.S. murder rate from the 1930s through the 1950s. “I certainly think it’s a reasonable exercise,” Miron says. “We just have to be appropriately suspicious of how much you can actually show.”

The theory will be put to the test as children grow up in Indonesia, Venezuela and sub-Saharan Africa, where leaded gasoline has just recently been phased out. Meanwhile, the list of countries that still use lead in gas — Afghanistan, Serbia and Iraq, as well as much of North Africa and Central Asia — does not rule out a connection with violence.

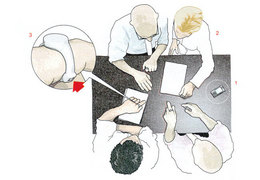

No matter how suggestive the economists’ data, it takes a doctor to show that some of the people most damaged by lead are out there breaking the law. Herbert Needleman, the University of Pittsburgh psychiatrist and pediatrician whose work helped persuade the government to ban lead in the 1970s, recently studied a sample of juvenile delinquents in Pittsburgh; the group had significantly more lead in their bones than their peers. And lead may not be the only source of damage. The National Children’s Study will soon begin to track more than 100,000 children to determine the effects of exposure to common pesticides, among other chemicals.

Jascha Hoffman is on the staff of The New York Review of Books.