WHEN RICHARD GOULD, an archaeologist at Brown University, took a walk in Lower Manhattan in October 2001, his trained eye fixed on a gravelly dust strewn on dumpsters and fire escapes that cleanup crews had missed. Looking closer, he saw that the coating contained bone fragments and other human remains mixed in with concrete dust and ash.

Gould, a founder of the subfield of ethnoarchaeology, which uses material culture to learn about living societies, immediately recognized that if this substance were properly sifted, it would help identify 9/11 victims. For that to happen, however, archaeologists accustomed to spending months scraping away on an isolated plot would need to go in just after the first-responders and be out of the way in time for cleanup -- "archaeology at warp speed," as Gould puts it.

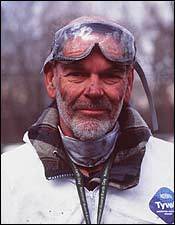

Back in Providence, Gould decided to act on his insight. Working with graduate students, the Providence police, and local volunteers, he formed the Forensic Archaeology Recovery (FAR) team in early 2002, pioneering a new subfield he calls "disaster archaeology." Like forensic archaeologists who examine crime scenes or mass graves, FAR would collect physical remains to try to piece together what happened to whom at a disaster site. But they would be prepared to dig faster and more thoroughly -- while using a stricter scientific protocol than conventional disaster response teams. Most importantly, unlike any forensic archaeologists before them, their main purpose would be to provide understanding and closure to survivors and families of victims.

Today, Gould's expertise is increasingly in demand by government officials from New York to Iraq,where his methods have been well-received by those who identify the bodies of American soldiers. And he is working to make FAR an official part of the Department of Homeland Security.

Still, the fledgling discipline of disaster archaeology remains largely beneath the scholarly radar. Some specialists scoff at the idea of do-good forensics, while others see Gould as extending the field's time-honored public-service tradition. Gould may modestly claim not to have any big answers, but his work raises a big question: Can archaeology serve scholarship, government, and the bereaved at the same time?

. . .

The first real test of Gould's approach came when tragedy struck close to home. In February 2003, when 100 clubgoers died in the smoke and flames of The Station nightclub fire in West Warwick, R.I., FAR was ready to swing into action. Gould had joined the federal Disaster Mortuary Response Team (DMORT) in the process of organizing FAR, and was now working around the clock with federal medical examiners to identify every last one of the victims in just three days -- a prodigious feat of speed and accuracy. Then the State Fire Marshal took Gould aside and explained that, to avoid the inevitable scavenging that occurs when the police tape is lifted, he wanted FAR to collect all personal effects and human remains left in the wake of the emergency workers.

Seeing a chance for FAR to prove that it could help authorities better provide closure to families, without interfering with emergency work or the ongoing investigation, Gould decided to take the assignment. FAR volunteers zipped up their white Tyvek suits and, under the suspicious gaze of survivors and television cameras, started gathering debris, searching for objects as small as earrings and teeth. They filled 340 buckets and recovered 88 clusters of objects in all, from guitar picks to supermarket frequent-shopper cards.

The work was grueling, the conditions were harsh, and the team often had to improvise. It was too cold for wet sifting, the standard technique used to spray debris loose from artifacts, so they had to chip away at icy chunks of ash instead. Because officials were still swarming the site, it was impossible to use the traditional string grid employed by archaeologists to record the exact positions of found objects. So they replaced it with a movable square made from PVC pipe, which they could line up with markings on the perimeter. When it snowed, they improvised a tarp.

To make things harder, the team had to meet police evidence-processing standards when handling the objects they recovered. At one point, while police were busy inspecting all area clubs for fire violations, Gould was given temporary oversight of the Mobile Crime Unit van where found articles were tagged as evidence. "I'm used to peer review," Gould said, "but legal scrutiny is worse."

The scrutiny has only gotten more intense. The team's fastidious procedures yielded some of the strongest clues as to the cause of the fire, and all of Gould's field notes were subpoenaed last year. With cases pending, he can't discuss the details, but he does mention an artifact he calls the "smoking gun." "Is this what you had in mind?" he recalls asking the chief of the team from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms that was independently combing the stage area for clues. The chief snatched it from his hand without so much as a word.

For Gould, a video shot inside the building as it burned down provided a unique opportunity to test the accuracy of his techniques -- and to improve them, by rewinding the film to figure out where to sift next. He notes that academic archaeologists, who are used to century-old sites with no written record, are not accustomed to this level of accountability. "When you excavate a Narragansett cemetery, no one can challenge your inferences," Gould says.

In the end, FAR may have raised the bar for forensic response to terrorism and other mass-casualty disasters. "They use trowels and screens where we use rakes and shovels," says Napoleon Brito, director of the Bureau of Criminal Identification at the Providence Police Department, now a FAR member himself. "They're much more accurate, much more patient."

Richard James, deputy State Fire Marshal of Rhode Island, agrees. "These young people were determined to bring closure. They were very professional. . .. They cleaned [the site] down to a bare floor."

. . .

At the age of 64, when many scientists might be thinking about retirement, Gould is on the lookout for the next opportunity to put his archaeological training to public use. Lately, he's been thinking about suicide bombers. On a recent rainy Saturday, FAR volunteers and Rhode Island police officers strapped a 5-pound dynamite vest to a dead sheep and detonated it inside a police car in order to practice their response. While the police worked within a 100-foot perimeter, Gould's team tracked car parts and significant chunks of flesh several hundred yards away.

Fellow archaeologists are divided on the significance of Gould's work. According to David Thomas, curator of North American archaeology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, disaster archaeology is the youngest branch of applied archaeology, which already extends to landfills, battlefields, and politically sensitive historical projects, such as the excavation of slave quarters at Monticello and Mount Vernon. "It fits within the broader sweep of recognizing that what you do matters to descendant communities," says Thomas, who plans to include Gould's work in the new edition of his undergraduate textbook.

Yet some think Gould's service orientation may cloud his scientific judgment. "If he's being utilized by law enforcement then he has to go by their rules," says Walter Birkby, a forensic anthropologist in Tucson, Ariz. Birkby also questions the originality of Gould's work. "He's not doing anything that's innovative. People have been doing this for years and years."

Jennifer Trunzo, a doctoral candidate in archaeology at Brown and FAR's deputy team leader, sees the team's originality not in its methods but in its mission. "We're just taking established excavation and recording skills and applying them in . . . public service," she says. This, she continues, "allows archaeology to give something back to the public that goes beyond heritage preservation."

"Sometimes a body cannot be returned intact for burial," Trunzo says. "But a wedding ring, a cell phone, or some other personal item can definitively tell people if . . . they should be mourning, rather than waiting for somebody to return that may never come home."

Gould hopes that FAR can eventually earn a permanent place on DMORT within the Department of Homeland Security. To that end he is trying to assemble a nationwide roster of on-call archaeologists under the auspices of the Society of American Archaeology. But he worries that, as officials discover the forensic power of his work, his team will be stretched beyond its modest humanitarian mission. He notes that while human-rights archaeologists are busy digging up mass graves in Iraq, no one is studying suicide bombings with the intent to repatriate items to grieving families. "The government's goal may not be the same as ours," he admits, "but someone should be doing this."

. . .

Last June, after the smoke cleared and every trace of The Station nightclub had been hauled away, 100 crosses made from the discarded tongue-and-groove floorboards, painted lavender and decked with plastic beads and butterflies, were erected around the perimeter. The next week brought waves of flowers, candles, statues, money, and unopened beer cans. Weeks later, someone had the idea of lining the entire site with solar-powered yard lamps. As the site blossomed into a full-scale memorial, it attracted more tributes, including fuzzy dice, compact discs, and model cars.

For Gould, these spontaneous memorials in West Warwick offered a chance to extend FAR's work in a new direction. And so he asked Randi Scott, a 50-year-old FAR volunteer from East Greenwich, to catalog the proliferation of objects and interview those who brought them.

As an ethnoarchaeologist who studied Australian aborigines in the 1960s, Gould was accustomed to doing a cultural anthropologist's work with an archaeologist's tools. Here was an opportunity to begin a formal study of the spontaneous memorial in an effort to understand the community's reaction to the tragedy through its rituals of grieving. So it was that Gould made the curious switch from conducting research for the bereaved to conducting research on the bereaved.

On a late February afternoon, just days after the one-year anniversary of the fire, Scott gave me a tour of the muddy lot. A few people hovered over particular plaques, and a young couple kissed as they stepped around puddles and shrines. Every so often, Scott stopped to prop up a cross that had been blown down, or to replace a picture that had drifted from its usual place. "I do this because I know where everything belongs," she said. "But I would never take anything away. This is a hallowed place."

It may seem odd that no official memorial is planned at West Warwick. Two doughnut shops and an oil-change station are interested in developing the site, Gould says, although he doubts anyone would frequent them. Meanwhile, plaintiffs' lawyers have put an injunction on the modest plot, in an effort to claim something of value for their clients. Most families, however, want to use the space for a public memorial. If they go to court, Scott says, they may use her documentation to prove the site has been under continuous use by mourners.

Gould denies that his mission is political or that it goes beyond the scholarly effort to understand. "We're not here to exert influence, but simply to observe and record," he says. But sometimes it seems that Gould and Scott are still combing the site because, like the survivors and families who show up every day, they are not yet free to leave.

"We just want to make sure we don't miss anything," says Gould.

—Jascha Hoffman